What Do You Want?

Why Wait?

S

Inconclusive

Prolix, endlessly digressive, a mass of description, theories that trail off into inconclusiveness, volume after volume, a flood of internal contradiction.

— Rosalind Krauss on John Ruskin, The Optical Unconscious

The Optical Unconscious

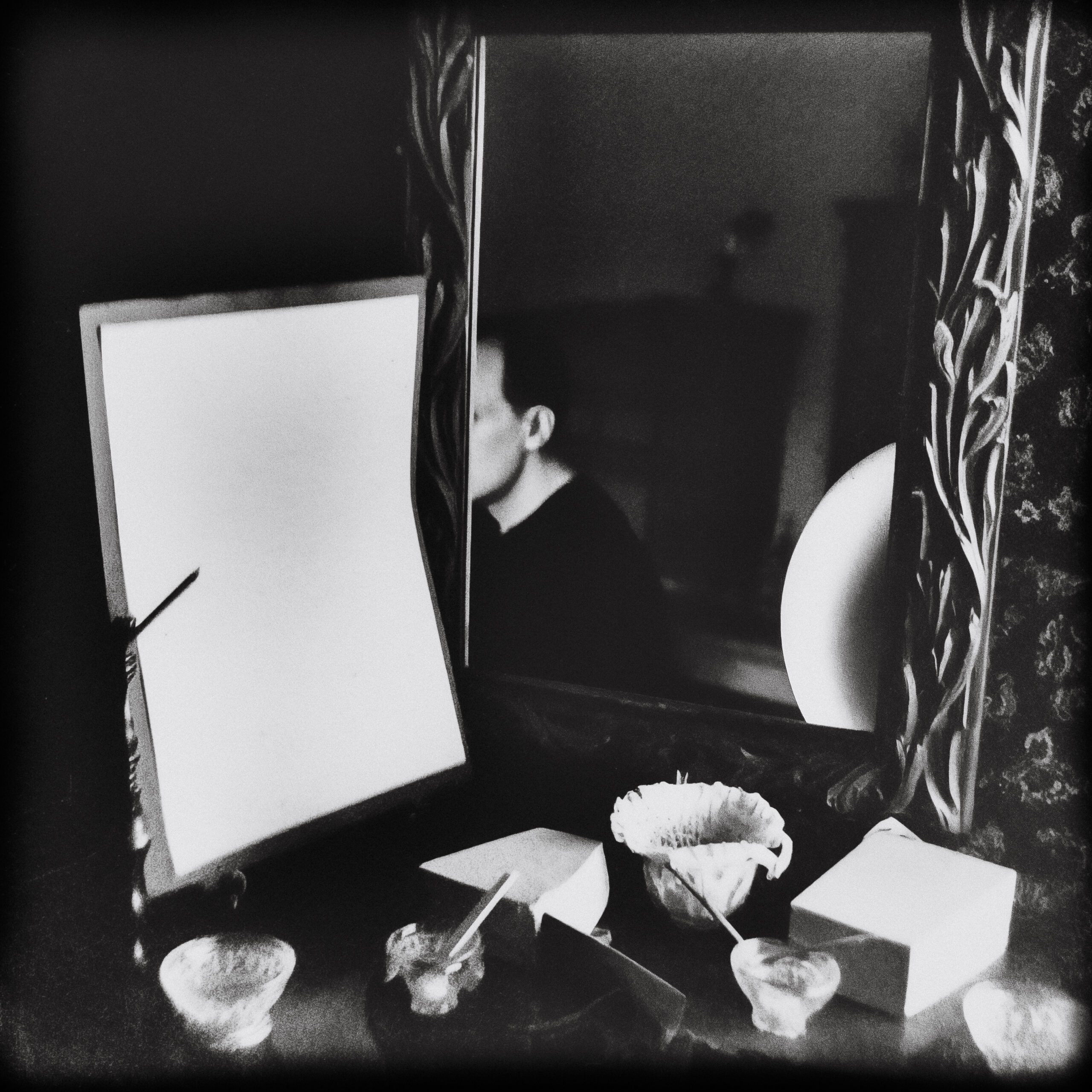

“another nature … speaks to the camera rather than the eye: “other” above all in a sense that the space informed by human consciousness gives way to a space informed by the unconscious. While it is commonplace that we have some idea about what is involved in the act of walking (if only in general terms), we have no idea at all about what happens during the fraction of a second when a person actually takes a step. Photography, with its devices of slow motion and enlargement, reveals the secret. It is through photography that we first discover the existence of this optical unconscious, just as we discover the instinctual unconscious through psychoanalysis.”

— Walter Benjamin, Kurze Geschichte der Photographie, 1931

8+6

Ludwigshafen, Juli 2024

Superflat

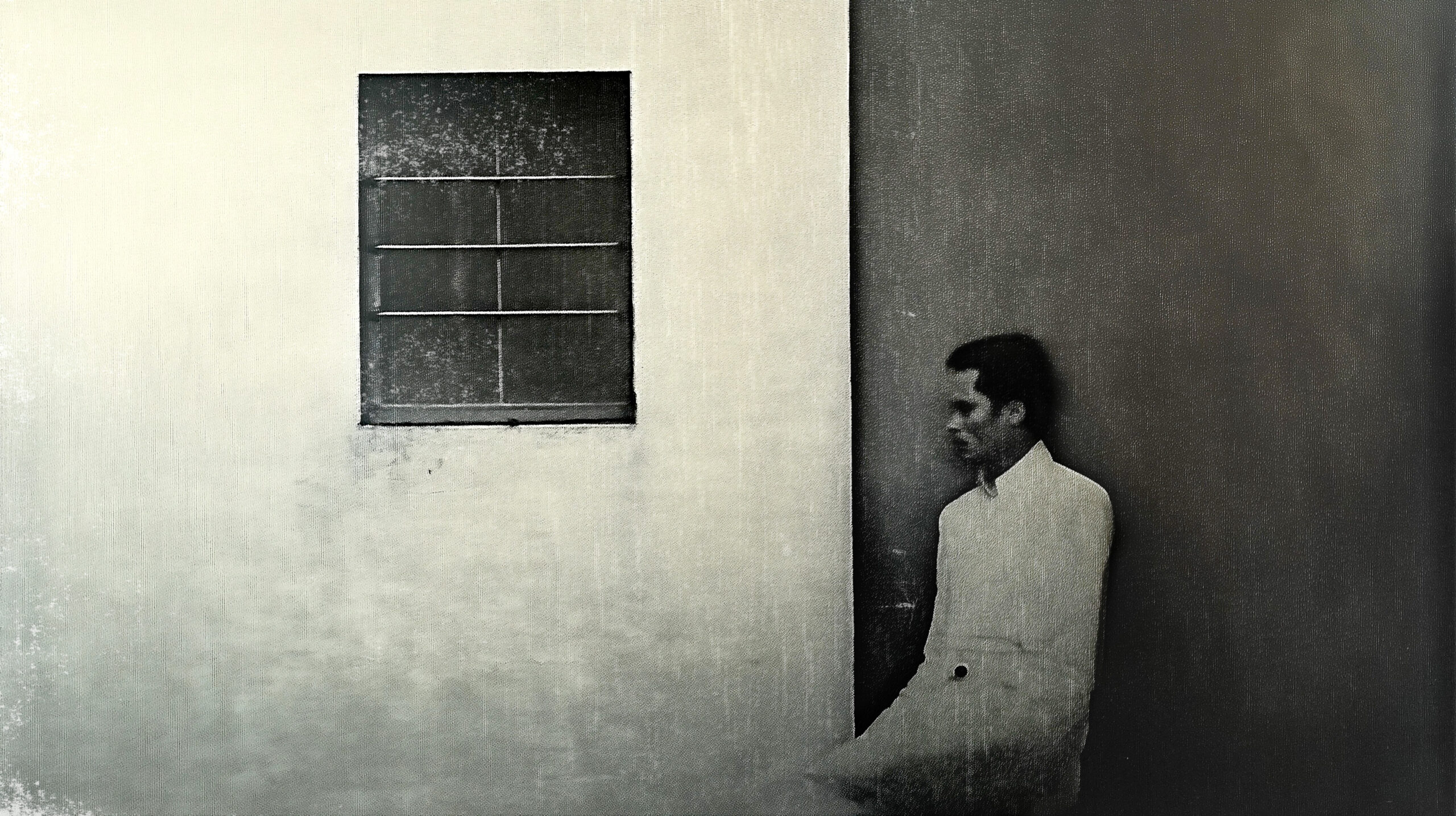

Twenty-three years later, I get the feeling that the act of allusion has replaced the act of expression. Day by day, we rely on a subtext that either vanished or never existed, collectively waiting for someone else to fill in the gaps of what we thought we meant to say. Overstimulated and still bored – ahh hell – even the clearest of images have become too much to bear.

Because the more we try to deny it,

the more we become aware,

that behind all representation

lies an empty vessel of despair.

Tragedy and the Superflat, Daniel Moldoveanum https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/articles/tragedy-and-the-superflat

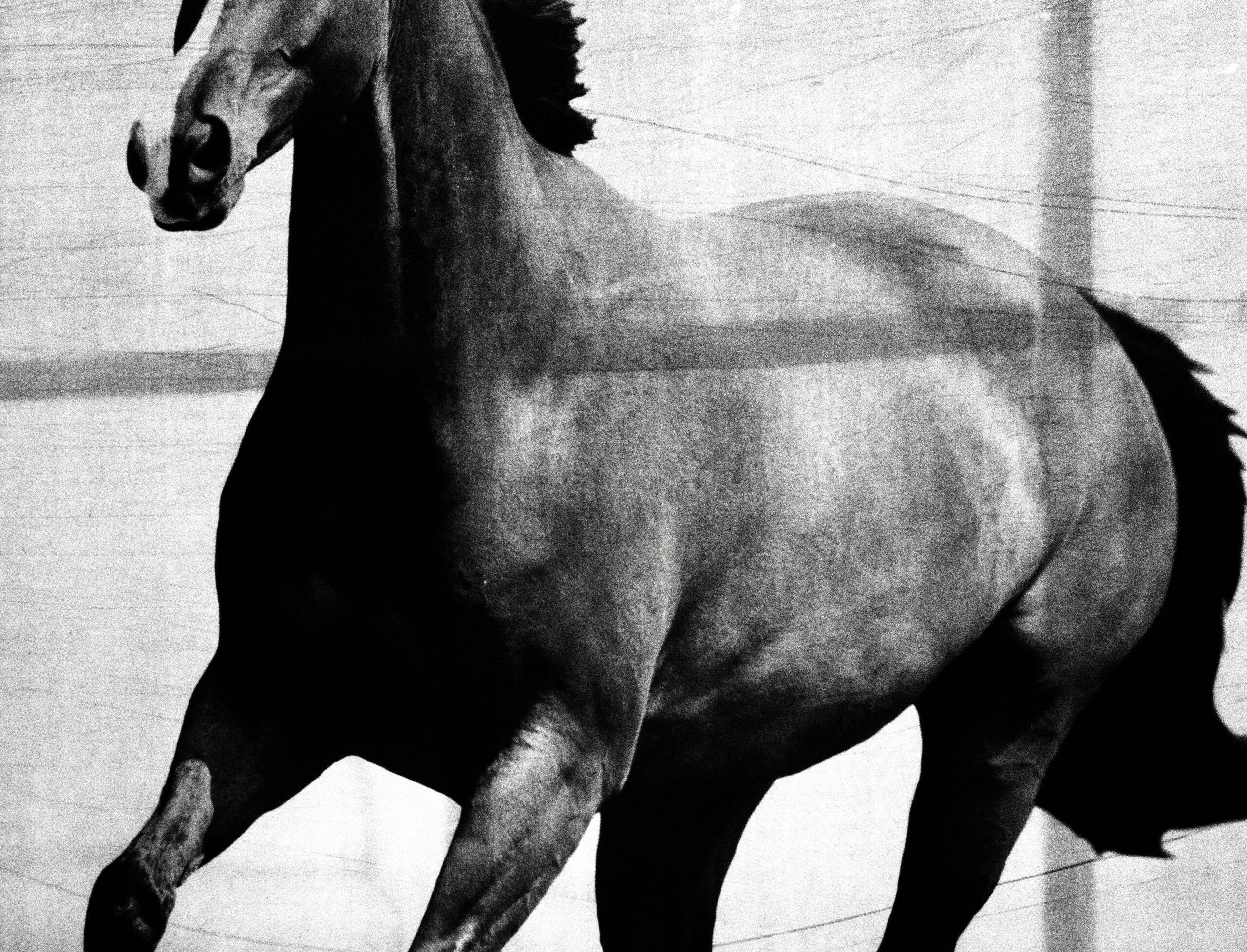

Shapes moving through the World

is it things moving through the world forming shapes, or is it shapes moving through the world forming things?

Nocturnes

LU. July 2024